By July of 1945, the United States was focused on ending the war with Japan as soon as possible. Germany had surrendered two months earlier, and American troops had been making concerted, albeit contested, advances towards the Japanese mainland. The Allies believed that they would eventually prevail, and began strategizing about the organization of the postwar world.

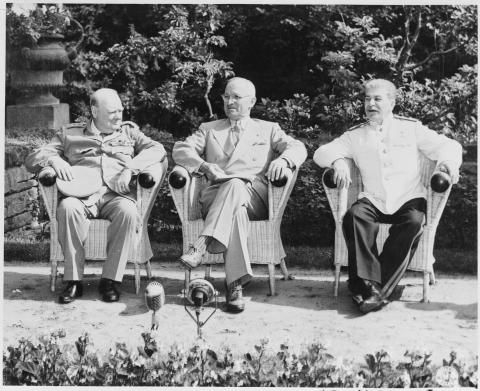

A major component of this process was the Potsdam Conference. Convened in a suburb of Berlin at the manor of a former German crown prince, the conference was attended by representatives of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. It represented the culmination of wartime meetings between the three countries. Amid the ruins of the former Nazi empire, the world’s temporarily allied superpowers set out to plan the conclusion of the war and the international framework of global peace.

Much of the conference was spent discussing the future of Germany and the reparations that would be imposed on it. Plans were also laid to establish a new Polish state and the governance of Southeast Asia. Simultaneously, much of the discussion at Potsdam was dedicated to finding ways to end the war with Japan. These deliberations were shadowed by the specter of the newly completed atomic bomb, which profoundly shaped the behavior of American officials at the conference as well as the diplomatic atmosphere of the world after the war.

International Climate Prior to Potsdam

President Franklin D. Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945. He was succeeded by his Vice-President, Harry S. Truman. Unlike Roosevelt, who had ably led the American war effort to that point, Truman was a foreign affairs novice. Soon after he was sworn in, he remarked to members of the press, “Boys, if you ever pray, pray for me now.” Not only was his experience on the international stage quite limited, but also he had largely been shut out of most of Roosevelt’s foreign policy decision-making. He entered the conference unsure of his ability to negotiate with seasoned global leaders like Josef Stalin and Winston Churchill.

Despite Truman’s anxieties about negotiating with such notable figures, it became increasingly clear in the months leading up to the conference that taking action to discuss the conclusion of the war would be necessary. Soon after the German surrender in May 1945, American troops began a long, bloody campaign to conquer Okinawa, the final island stop remaining before the Japanese mainland. In the months before the Potsdam Conference, the United States Army Air Forces, led by General Curtis LeMay, had begun a firebombing campaign attacking major Japanese cities. With the European Theater of the war concluded, Japan had the attention of the world, and Allied leaders wanted to end the war there as quickly as possible. This prospect required careful orchestration, given the intensity of Japanese efforts thus far to defend their territory in the Pacific.

Another wrinkle that impacted the organization of the conference was the political situation in Britain. Although Winston Churchill and the Conservative Party were expected to do well in the 1945 elections, they were upset by Clement Attlee and the Labour Party. Attlee accompanied Churchill at Potsdam while they awaited the results of the election, which became known during the conference. This shift in leadership meant that Stalin was the only head of state present for the entire conference who had been in office for the duration of the war. As such, he possessed considerably more experience negotiating on an international stage than his counterparts.

The Trinity Test

Truman’s relative lack of participation in wartime decision-making during his tenure as Vice-President limited his knowledge of the Manhattan Project. Details of the project only became available to him after he was sworn in. As President, he was initially skeptical about the bomb’s feasibility as a weapon. His original initiatives for the Potsdam negotiations were all crafted under the assumption that the United States would not be able to use the bomb at all. As such, the plans designed by Truman and his advisors before the Potsdam Conference were based on an invasion of the Japanese mainland. The invasion would require both American and Soviet forces.

Few members of the Truman administration were enthused by such a reality. Many officials who were wary of the Soviet Union’s decidedly undemocratic policies were loath to give it the opportunity to expand its East Asian sphere of influence by allowing it to partake in the invasion of Japan. Seeking any possible alternative, Truman was able to successfully stall the beginning of the conference until mid-July in the hope that Manhattan Project officials would be able to prove the efficacy of the bomb by that point.

In a stroke of luck for American negotiators, the Manhattan Project successfully conducted the Trinity Test, the first nuclear test in history, on the morning of July 16, 1945. Its effects on the rest of the world would reverberate far beyond the test site in the remote New Mexico desert. News of the top-secret test’s success was immediately telegraphed to Truman, who by that point had already arrived in Germany for the conference. Although he was pleased with the result of the test, it was not until the end of the week when he received a detailed report on it from General Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project.

Truman was emboldened by the success of the Trinity Test. The addition of nuclear weapons to the American arsenal fundamentally strengthened his position at the negotiating table. Aides recalled that Truman felt a renewed sense of optimism after that point in the conference. Secretary of War Henry Stimson described him in a diary entry as “pepped up.” The success of the Trinity Test was basic to the ensuing American strategy for concluding the war in the Pacific. The atomic bombs gave the United States the opportunity it sought to end the war with Japan without having to rely on Soviet troops for a ground invasion.

The Soviet Question

James F. Byrnes, the incoming American Secretary of State and one of Truman’s most trusted confidants, was adamant that the atomic bomb be utilized against the Japanese as soon as it became possible to do so. Many members of the Truman administration, including Byrnes, advocated for using the bomb as a way to avoid Soviet entry into the war with Japan. This express desire to end the war as quickly as possible was shared by Truman. Some historians have argued that it is the reason that the bomb was used so quickly in combat after its initial test, and why the second bomb was dropped so shortly after the first. However, that decision is a topic of significant controversy, and historians have not reached a consensus on the exact motivation for the bomb’s timing. Historian J. Samuel Walker argues that Truman’s singular desire to end the war was motivated by a need to protect the lives of American servicemen.

Another issue raised at Potsdam was the notion of international arms control. Some members of the Truman administration, and several scientists who had worked to create the bomb, believed that the Soviet government should be made aware of the atomic bomb. They argued that including the Soviets at this level of the bomb’s development would help diminish needless antagonism between the two governments after the war. Ultimately, Truman was inclined to share with Stalin the fact that the United States possessed a nuclear weapon in order to strengthen his bargaining power at Potsdam.

Another issue raised at Potsdam was the notion of international arms control. Some members of the Truman administration, and several scientists who had worked to create the bomb, believed that the Soviet government should be made aware of the atomic bomb. They argued that including the Soviets at this level of the bomb’s development would help diminish needless antagonism between the two governments after the war. Ultimately, Truman was inclined to share with Stalin the fact that the United States possessed a nuclear weapon in order to strengthen his bargaining power at Potsdam.

Truman’s desire to demonstrate the new capability of the American military was tempered by wartime insistence on secrecy. However, he was able to find a moment at the conference to vaguely mention the bomb to Stalin. Finding a moment when both men were alone, Truman casually mentioned to Stalin that the United States had developed a new weapon of unprecedented power. He gave Stalin no specifics about what that weapon was, and certainly no information on how it was made or where and when it would be deployed. The Soviet leader responded with equal nonchalance, remarking to Truman that he hoped that the weapon would be put to good use against the Japanese.

Stalin’s seeming lack of interest in Truman’s supposed trump card came as a surprise to the American officials at Potsdam. They were unaware that Stalin had already known about the American effort to build an atomic bomb, via the Soviet spy network. In fact, Stalin had known about the existence of the Manhattan Project for longer than Truman. Such a revelation would have shocked the American officials at Potsdam, who adamantly refused to share knowledge of the Manhattan Project with the Soviets.

The Potsdam Declaration

On July 26, 1945, midway through the Potsdam Conference, American, British, and Chinese leaders issued a proclamation to the leaders of Japan demanding their unconditional surrender. Although Chinese leaders were not present at the conference, communication was kept up with Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Chiang Kai-shek throughout.

While still wanting to end the war quickly and vigorously, the declaration noted that the Allied powers had no desire to destroy the nation of Japan or enslave its people. The terms of the surrender included the abdication of Japan’s military government, while forcing it to rescind its claims to territory in the Pacific beyond the main islands of Honshu, Kyushu, Hokkaido, and Shikoku. It also asserted that there would be an Allied presence in Japan until it was demilitarized and established as a Western trading partner.

It is notable that the Soviet Union was not included in the declaration, despite having representatives at Potsdam. Technically the USSR was not yet at war with Japan, and would not declare war until August 8, 1945. The American delegation to the conference was particularly reluctant to entertain Soviet assistance. Their desire to limit the Soviet Union’s Asian sphere of influence set the tone for the Cold War, even before World War II came to a close. Any American-Soviet cooperation in the war against Japan would have constituted a fraught and uneasy continuation of the wartime alliance.

The atomic bomb received scant description in the declaration itself. After listing the terms of surrender, the document concludes by saying, “The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.” As with Truman’s veiled mention of the bomb to Stalin during the conference, American officials opted not to compromise the carefully cultivated security of the Manhattan Project. More than 70 years later, historians continue to debate whether the United States should have more explicitly warned the Japanese about the consequences of refusing to surrender. Many members of the scientific community, including several Manhattan Project contributors, felt that the Japanese should have been more frankly warned about what exactly was about to be unleashed.

To read the entire Potsdam Declaration, click here.

Lasting Consequences

The Japanese did not initially accept the terms of surrender offered in the Potsdam Declaration. Many Japanese officials were reticent about the declaration due to its demand for “unconditional surrender.” This was seen as confirmation that surrender would result in the deposition and even execution of the revered Emperor Hirohito. Such a possibility made Japanese acceptance of the declaration practically impossible.

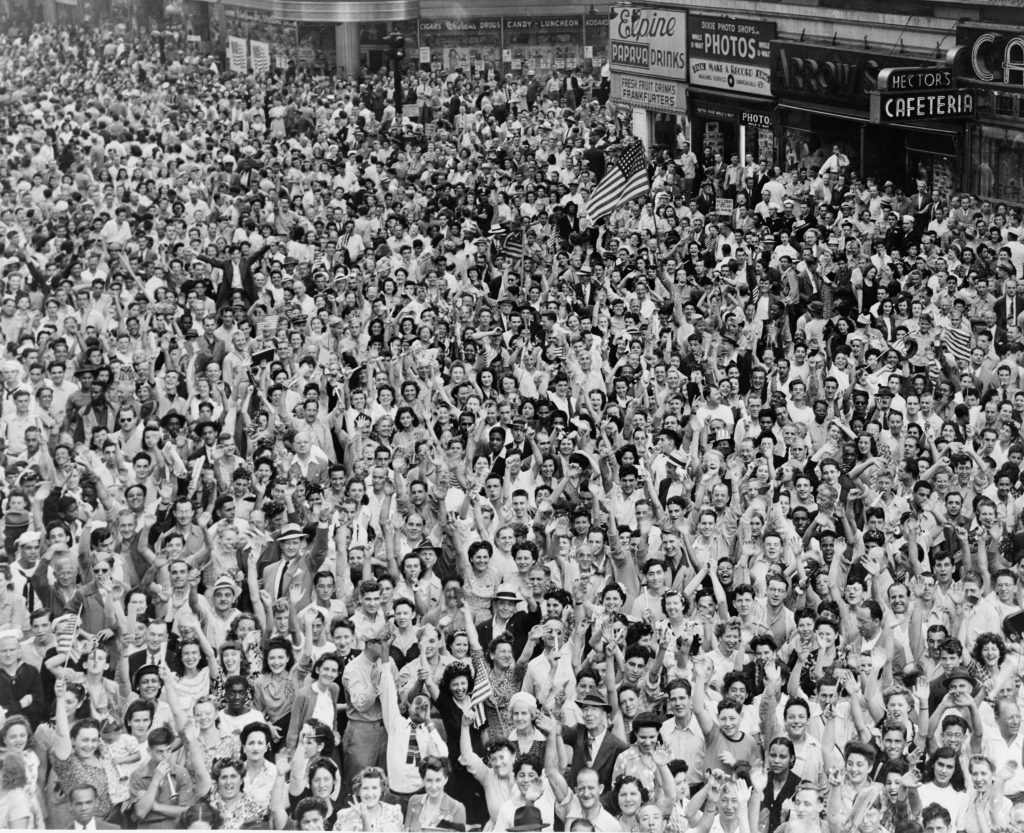

To force the Japanese to surrender, the United States became the first and only nation to use nuclear weapons in combat, dropping atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki within a week of the close of the Potsdam Conference on August 2, 1945. Soon after, the Japanese agreed to an amended version of the Potsdam Declaration that came with assurances from Truman that the Emperor would be allowed to remain in power. World War II was officially over.

The events of the Potsdam Conference proved to have a far more lasting impact on the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union. The relationship between the two countries had been tenuous throughout the war. That internal division was evident in the decision-making of the American officials who so desperately sought to avoid Soviet intervention in the war’s Pacific Theater. The success of the Manhattan Project made the atomic bomb the most important bargaining chip in achieving that end. Therefore, some historians argue that the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the first shots of the Cold War, as well as the last shots of World War II.

For more information on how the Potsdam Conference related to use of the atomic bomb, please refer to AHF’s annotated bibliography on the debate over the use of the bomb.