In May of 1950, a 32-year-old FBI agent named Robert Lamphere came face-to-face with Klaus Fuchs. The Soviet spy was “very reserved,” Lamphere recalled. “Somewhat shy, perhaps a touch of arrogance underneath the shyness. Right off the bat, he wasn’t sure he wanted to tell me anything.”

In 1994, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and AHF Board member Richard Rhodes conducted three interviews with Lamphere. These interviews are available on the Voices of the Manhattan Project website. Lamphere’s recollections provide a dramatic firsthand account of the FBI’s efforts to uncover Soviet espionage during the early years of the Cold War.

Born in Idaho, Lamphere joined the FBI in 1941 after graduating from law school. He quickly showed promise as an investigator. After a stint in Birmingham, AL, he was assigned to New York City. In 1947, he was transferred to FBI headquarters as a Supervisory Special Agent, and took charge of counterintelligence related to Soviet satellite countries.

As Lamphere found his way into counterespionage, the U.S. Army Security Agency, a forerunner of the National Security Agency, was making alarming discoveries about the extent of Soviet espionage in the United States. Even though the US and the USSR were allies during World War II, both powers distrusted each other. In 1943, the Army Signal Intelligence Service had created the top-secret “Venona” project to decode Soviet intelligence cables. Analysts realized that the Soviets had reused some of the one-time pads they employed to send encrypted messages, making it possible to decipher parts of the code. In 1946, cryptologist Meredith Gardner began to break into Soviet trade messages and pieced together information about a wide-ranging espionage network in the United States, including Soviet spies on the Manhattan Project.

As the importance of the decoded messages became increasingly clear, Lamphere was named the FBI’s liaison to Venona. When asked why he was tapped for the position, Lamphere remarked, “I sometimes wonder myself. Well, I was a good writer. I could write in the style that they liked, and I never had any trouble making decisions… I was brought in not because anybody thought I was ready for greater things, but because I was considered a good espionage investigator.”

The collaboration between the introverted Gardner and the hard-charging Lamphere was essential to exposing Soviet spying on the Manhattan Project. An important breakthrough came in 1948, when Gardner requested that the FBI send copies of intercepted Russian commercial messages from 1944. Lamphere recalled, “The next time I saw him, which was about two weeks, was the most excited that I ever saw him in my life…We hit it right on the nose.” These messages helped Gardner make major progress in breaking the Soviet code.

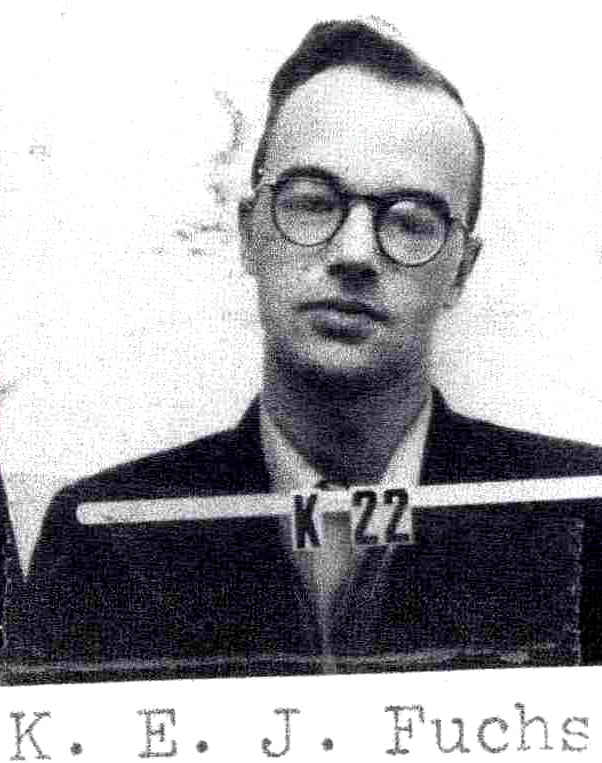

The spy ring began to unravel when Venona uncovered a report written by Fuchs on the atomic bomb project. A German émigré, Fuchs joined the British Mission during the Manhattan Project and was a member of the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos. He had worked on the implosion design for the plutonium bomb, and had passed detailed notes about it to the Russians. In 1946, Fuchs returned to the United Kingdom and became head of the theoretical division at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell.

Confronted by British intelligence, Fuchs confessed. Meanwhile, Lamphere intensified his search for Fuchs’s courier, code-named GUS or GOOSE in the Venona transcripts and known to Fuchs as “Raymond.” Lamphere recalled the seeming hopelessness of the search: “We knew from [British interrogation of] Fuchs that the guy had some kind of a chemistry background. We were looking to see how many chemists were in New York City. There was fifty thousand or seventy-five thousand or some such number. The description seemed to fit about two million American men. The instructions that were coming down to me from on high: ‘What are you doing to find this guy? What’s taking you so long?’”

After negotiations with the British government, Lamphere was allowed to come to London to interrogate Fuchs. Lamphere remembered it as “the hardest thing I probably ever did in my life.” Nevertheless, on May 22, 1950, he notched another breakthrough. When Lamphere showed Fuchs photographs of one suspect, a chemist named Harry Gold, Fuchs identified Gold as “Raymond.”

Over the next few weeks, Lamphere and the FBI worked around the clock to identify the other members of the spy ring. Gold confessed his involvement, and implicated a Manhattan Project veteran and machinist named David Greenglass. Greenglass’s arrest led to the identification of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

The break-up of the spy ring caused a furor. The Red Scare was already at a fever pitch, and the arrest of the atomic spies confirmed many Americans’ fears that espionage had allowed the Soviets to produce their first atomic bomb. Fuchs, Gold, Greenglass, and the Rosenbergs were all convicted of espionage. The first three received prison sentences; the Rosenbergs were executed in 1953.

To some degree, Lamphere understood the motives of the spies he helped apprehend. “You see the anti-fascist aspects of it, and the evil of Hitler, and you can understand that part of it.” He opposed the execution of Ethel Rosenberg, but had little sympathy for her and her husband. “You look at the Rosenbergs and look at Fuchs, you’d say, ‘How could these people be so stupid?’”

Nevertheless, Lamphere disapproved of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s bullying. “I think McCarthy did more damage than anybody else to the honest cause of anti-Communism. Nobody could’ve hurt us as much as he did.”

After leaving the FBI in 1955, Lamphere became an executive with the Veterans Administration and senior vice president of the John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company. In 1986, he published a memoir of his experiences called The FBI-KGB War. Lamphere died in 2002.

The Venona project was not fully declassified until 1995. New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who helped make the Venona materials public, called Gardner and Lamphere’s collaboration an effort “that Americans have a right to know about and to celebrate.”

Click here to listen to Rhodes’s interviews with Lamphere. Visit AHF’s article on espionage to learn more about the spies who revealed Manhattan Project secrets.